"We see the forest as a mother. We respect what is there, but we take from it with careful management. We are not just taking and destroying—we have a very respectful relationship with nature."

waxamani mehinako

-

Patterns of Connection

In Brazil’s Alto Xingu territory, artist Waxamani Mehinako transforms ancient patterns into powerful visual stories that connect tradition and modernity. Each geometric line he paints carries the memory of his ancestors and the vision of a future where Indigenous culture is seen, respected, and shared. “I want to connect cultures through my work,” Waxamani says. “To share my heritage with everyone.” His name, meaning unique, was chosen by his father—a reflection of the path Waxamani continues to carve.

Rooted in Culture

Waxamani was born and raised in Kaüpüna village, where the rhythms of daily life follow the forest. His mother is Aweti, his father Mehinako, and both passed down values of resilience, purpose, and deep connection to nature. Now 31, he lives simply—painting, fishing, playing soccer, and tending to the land that fuels his creativity. “When I leave the village to work, I suffer. I miss the freedom and peace of home.”

-

A Visual Language

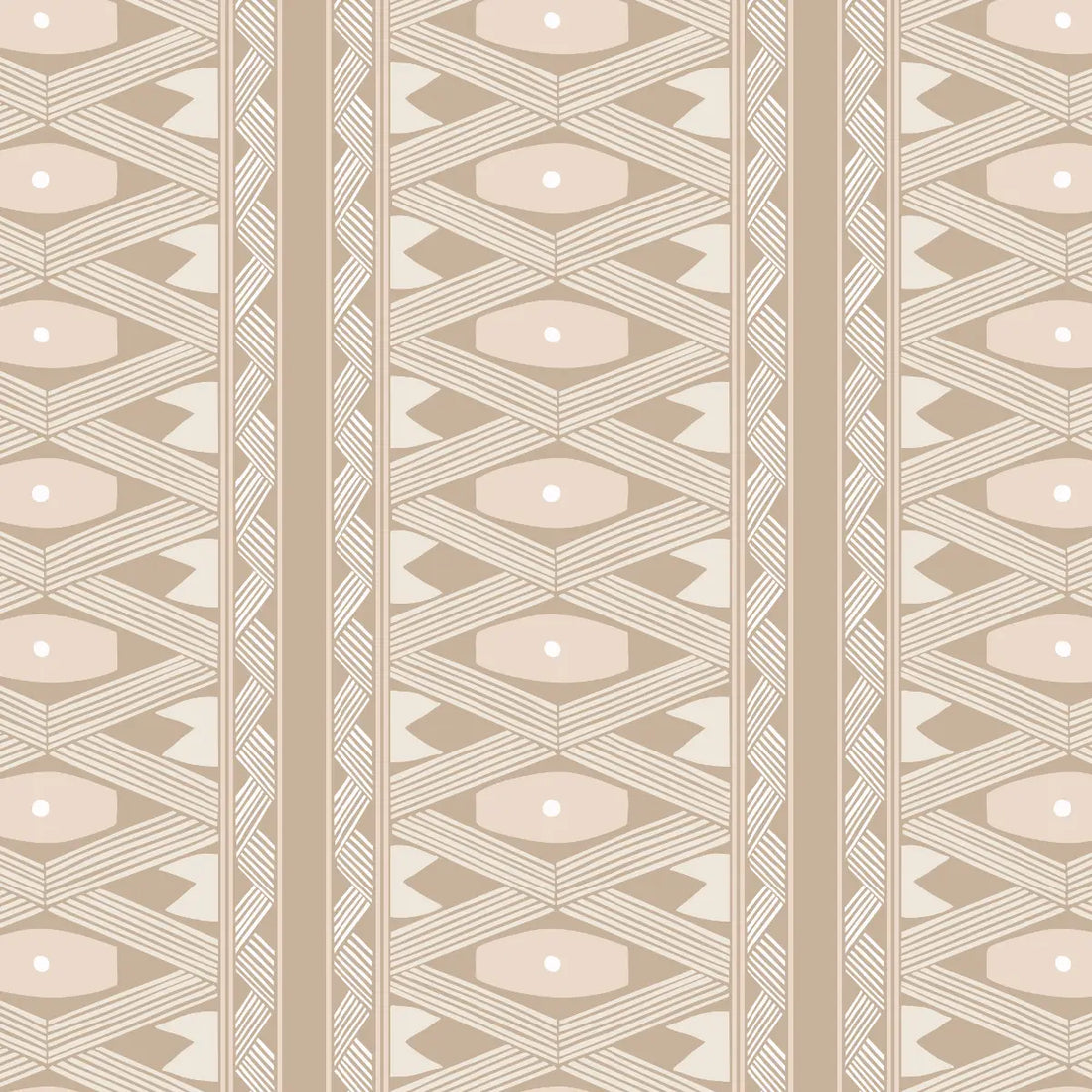

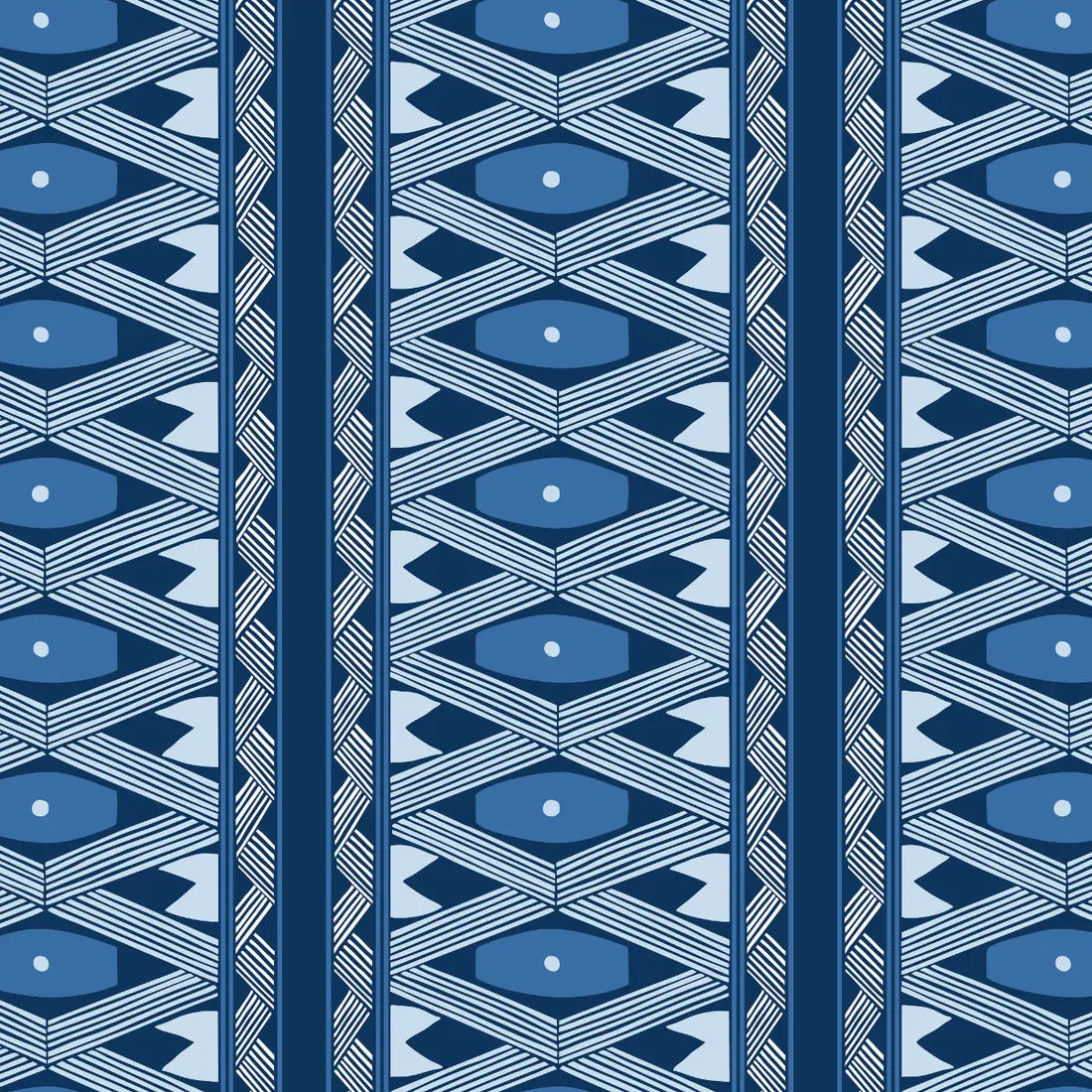

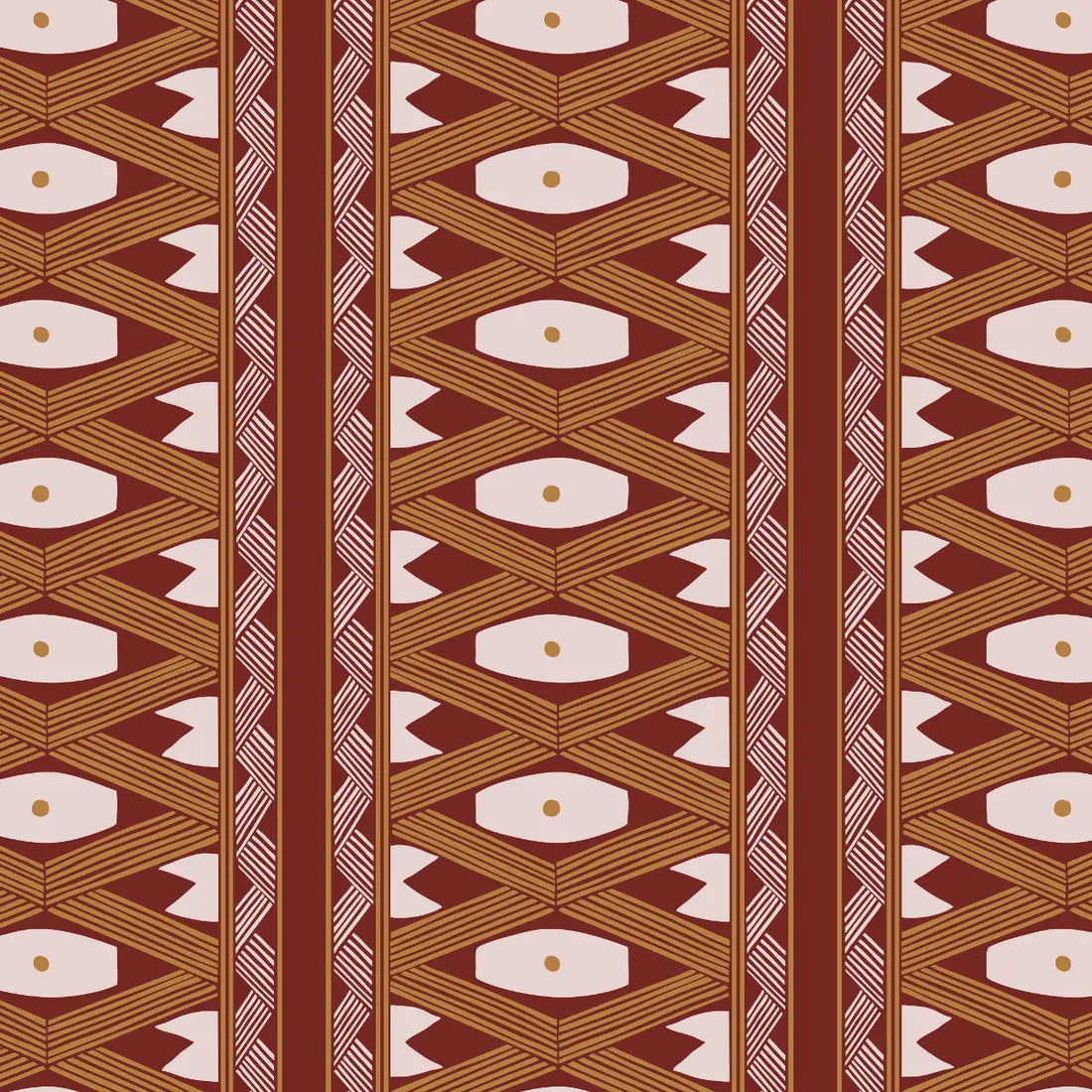

From an early age, Waxamani noticed that the patterns painted on bodies, textiles, and ceremonial objects held deep meaning—symbols of nature, protection, and history. “All our paintings are connected to nature. Everything has a story behind it.” In 2019, he made a bold choice: to focus entirely on the graphic patterns themselves, rather than using them to decorate other objects. This shift marked a turning point. Today, he coordinates a collective of 10 Indigenous artists, preserving tradition while pushing creative boundaries.

Nature as Material, Nature as Guide

Waxamani crafts his own pigments using traditional techniques—black ink from charcoal and inga tree milk, red from urucum seeds. These natural materials reflect the respectful, reciprocal relationship Indigenous people have with the forest. “We see the forest as a mother. We respect it, manage it, and never take more than we should.” This reverence also shapes his designs. His Walakuyana pattern—known as the “eye of the piau fish”—appears in one of his wallpapers. The fish symbolizes purification and guidance. “When we paint with these graphics, we feel the spirit of the fish protecting us.”

-

Art as Peaceful Resistance

Waxamani uses art as activism—an invitation, not a confrontation.“We’re not shouting. We’re protesting through our art.” His work raises awareness of environmental threats and Indigenous rights, not with slogans, but with beauty, truth, and cultural memory. His collaboration on recycled plastic wallpaper, for example, transforms waste into something sacred. “It gives new life—turning trash into artwork.”

-

Looking Ahead

Despite international recognition—including exhibitions at the São Paulo Biennial and collections in Europe, Australia, and the U.S.—Waxamani remains grounded. The city may offer exposure, but the forest is where he belongs. “I want people to respect our culture and our graphics. These paintings are ours—they carry meaning.”

Through his work, Waxamani Mehinako brings Indigenous knowledge into new spaces, building bridges between worlds with every brushstroke.

"All our paintings are connected to nature. Everything we have has a story behind it. I want people to feel the cultural value that exists behind these graphics—they aren't just patterns without meaning."

waxamani mehinako